Immigrants are worrying about social ties and finances during coronavirus

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Carlo Handy Charles, McMaster University

A recent Statistics Canada study reveals that immigrants and refugees are more likely than Canadian-born individuals to be worried about the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

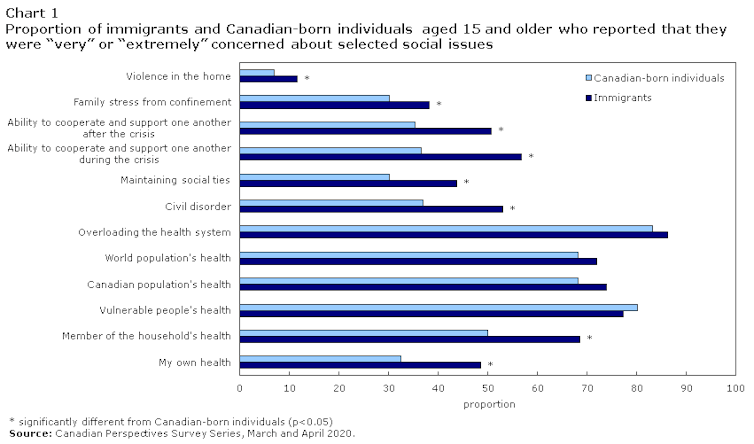

Forty-four per cent of immigrants reported having high levels of concern about the maintenance of social ties and their ability to support one another during or after the pandemic ; 30 per cent of Canadian-born individuals reported the same. The study confirms that differences between immigrants and Canadian-born individuals are similar for both men and women.

Immigrants — often racialized women and men from the Global South — have become the backbone of the Canadian economy and labour force during this crisis. They have filled low-paid jobs such as taxi drivers, farm workers and front-line caregivers.

These are jobs that Canadian-born individuals avoid. Immigrants often take on these jobs not because they lack professional qualifications, but due to lack of opportunity, non-recognition of their educational credentials or a lack of “Canadian experience.”

Canada is an immigration country and a world leader with respect to immigrant and refugee resettlement. While all individuals in Canada are coping with the impacts of COVID-19, it is crucial to understand how immigrants and refugees are experiencing the pandemic and how to help cushion its impact.

Immigrant status and social ties

Landed immigrants, refugees, migrant workers and international students may have different migration experiences but their status as foreign-born or non-national individuals have similarities, especially when looking at their social ties during the pandemic.

In Canada, immigrant social ties are often understood as memberships to Canadian recreational or religious organizations. However, research also shows that local networks of acquaintances, friends and services — sometimes ethnic, sometimes multi-ethnic or neighbourhood networks, and various community groups — contribute to and strengthen immigrant social ties.

Before COVID-19, some immigrants already missed the kinds of human interaction they were used to in their home countries – such as familiar faces, greeting friends and familiar products in stores. Previous research has shown that elderly immigrants struggle with social isolation and loneliness more than people born in Canada.

Social isolation resulting from immigrant status is an important determinant of immigrants’ physical and mental health. It is therefore important for governments and civil society to understand how their unique experiences during the pandemic may impact their health outcomes and well-being more than those of Canadian-born people.

Refugees’ concerns about social risks

Immigrants, especially refugees, are also more concerned than Canadian-born individuals — 53 per cent compared to 37 per cent — about the possibility of civil disorder during the pandemic.

Although they have different social networks than those born in Canada, refugees may be more sensitive to certain social risks, such as civil disarray or the ability to support each other.

Many refugees lived in camps, were held in detention centres or transited through various countries before accessing permanent legal status in Canada. In my research, I have found that some Haitian asylum-seekers had made an arduous 11,000-kilometre journey from Brazil to the U.S. — often on foot and under difficult circumstances — to claim refuge in Canada.

(Shutterstock)

This affects refugees’ health, and may also reactivate some trauma related to their pre-migration and migration journeys. This pandemic is a period of high uncertainty and social risk ; refugees may find themselves reliving some traumatic experiences, as research has shown on the experience of Syrian refugees or the Vietnamese “boat people” who came to Canada.

Research on influenza suggests that refugees and asylum-seekers may be required to adjust to a double coping strategy during pandemics. First, they must comply with public health measures, such as physical distancing. The second is their adjustment to potential traumatic migration experiences and social stigma. It is expedient to pay attention to how social stigma may affect refugees.

Concerns about socio-economic impacts

Immigrants are also significantly more likely than Canadian-born individuals to report that the crisis would have a “major” or “moderate” impact on their finances. While 27 per cent of Canadian-born men reported that the crisis would have an impact on their ability to meet financial obligations, 43 per cent of immigrant men reported the same.

The most recent labour market figures for April show that Canada lost nearly two million jobs in sectors like construction, manufacturing, retail trade, accommodation and food services. For immigrants, refugees and asylum-seekers, a job loss increases their precarity, especially among refugees who have been undergoing a decrease in earnings over the past 15 years in Canada.

At the same time, precarious employment is on the rise with vulnerable populations like immigrants and refugees who face higher rates of marginalization than Canadian-born individuals.

In the areas of Toronto and Montréal where there is a greater proportion of low-income earners, new racialized immigrants and high unemployment rates, residents have higher rates of infections and hospitalizations than people in other parts of those cities.

No matter how long immigrants and refugees have lived in Canada, their foreign-born status may affect them more than Canadian-born individuals during and after the pandemic.

Potential remedy

Some countries have used the pandemic as a pretext to deny basic human rights to migrants by implementing deportations or propagating social stigma.

This may add to immigrants’ and refugees’ concerns about the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 on their lives. To help mediate these impacts in Canada, we should recognize the vital contribution of immigrants, refugees and other migrants as some of the heroes of the pandemic.

Federal, provincial and municipal governments in Canada must adopt the 14 principles of protection for migrants and displaced people during COVID-19 ; written by migration experts, they provide a basis for advocacy and education during the pandemic.

Now more than ever, as migration researcher Steven Vertovec writes, migrants deserve empathy. To promote empathy, governments and civil society should elucidate structural and socio-economic conditions and vulnerabilities faced by many migrants and refugees, just as the UN Development Programme and the International Labour Organization are doing with regard to COVID-19 and people subject to poverty worldwide.

Whether they’re refugees, newcomers or other migrants, they are front-line workers who not only sustain the Canadian economy but also allow others to remain safely isolated at home.

Therefore, it’s imperative that federal and provincial governments consider the unique challenges faced by immigrants and refugees as they implement policies to help people in Canada recover from the impacts of the pandemic.![]()

Carlo Handy Charles, Vanier Scholar, Trudeau Foundation Scholar and Member of COVID-19 Impact Committee, CI-Migrations Fellow, and Joint Ph.D. Student in Sociology and Geography, McMaster University

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.

The Conversation

The Conversation